Originally Authored at TheFederalist.com

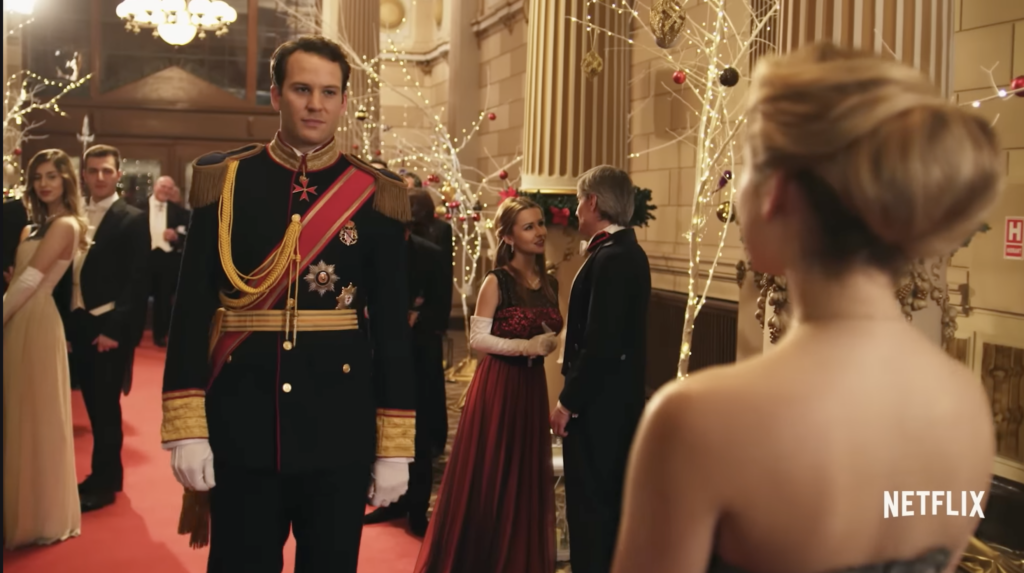

Since 2017, Netflix has constructed a Christmas rom-com cinematic universe, which now includes more than a dozen films, but its twin anchors are a pair of royal-themed trilogies set in the present day.

Conjuring up the raw materials the plots demand — monarchies and picturesque snowy villages — has forced Netflix to invent two European countries: Aldovia (where a New York journalist meets her “Christmas Prince”) and Belgravia (where Vanessa Hudgens’ baker character agrees to a “Princess Switch” with her royal doppelganger).

Neither of these is meant to be more than a stage set for the female fantasy of putting on a pretty dress and dancing with a prince in a cozy Christmas castle. But as a male history nerd whose wife forced him to watch these terrible movies, my mind immediately went to a very different place.

Behind all that cocoa-sipping frippery must lie the hard Thucydidean realities of diplomacy and war.

The Map

The biggest hint we get about the geopolitics of the Netflix Christmas universe comes in “The Christmas Prince 3: The Royal Baby,” when courtiers brief Queen Amber on a ceremonial treaty renewal with the (equally fictional) kingdom of Penglia.

Up to this point in the trilogy, I’d assumed that these fictional nations were tiny nonentities like Monaco or San Marino — existing for centuries without meaningfully influencing world history.

Then, we see the map (which is just the names and borders of Aldovia, Belgravia, and Penglia superimposed onto a page from a 16th-century Dutch atlas).

Frustratingly, it does not show any other countries. What it does show is that all three nations are major powers. Aldovia covers modern-day Austria, Czechoslovakia, the Balkans, northern Greece, and Turkish lands west of the Bosporus. Belgravian territory corresponds in our timeline to Lithuania, Latvia, eastern Poland, Belarus, and western Ukraine. Penglia covers Caucasian Russia, Georgia, Armenia, and Azerbaijan.

The History

Aldovia

Aldovia is a successor state to the Latin Empire that the 4th Crusade established after sacking Constantinople in 1204. The real Latin Empire lasted less than 60 years, but in the Netflix Christmas timeline, it endured, gradually reclaiming old Byzantine lands in Southern Europe.

The Latin Empire’s Catholicism explains why King Richard and Queen Amber are married in a church that lacks an icon stand (or iconostasis). It also explains why Greece isn’t part of Aldovia: they remained stubbornly Orthodox and, at some point, won independence.

My theory even accounts for why Aldovians speak English, wrote their medieval chronicles in the same language, and are ruled by royal houses called Devon and Charlton. In our timeline, when Constantinople fell to the crusaders, their leaders named Count Baldwin of Flanders as the new emperor. But what if some ambitious English nobleman had joined the Crusade and got himself crowned instead? Over time, the new royal house would have drawn more Anglophone knights and clergy to the east, solidifying English as the language of the court and (eventually) the people.

The empire would also gradually shed its Roman imperial pretensions, styling its ruler a “king” and taking as its new name the word “Aldo” — Old High German for “old” and “noble.” Rome lives on as, simply, the “Grand Old Kingdom.”

Penglia

The trickiest thing about Penglia is explaining why they’re East Asian. The medieval prince who fought Aldovia was named Jun, while the current king and queen are Tai and Ming — all Chinese names. The Penglian side of the treaty also appears to be written in Chinese characters.

The best explanation for this begins with China’s Yuan dynasty, which the Mongol warlord Kublai Khan established in 1271. In our timeline, the Mongol Empire quickly disintegrated into four independent states, with powerful Khans refusing to recognize the Yuan emperors’ overlordship.

In the Netflix Christmas universe, Yuan leadership manages to hold the empire together while establishing Chinese as the universal language of government, but are still overthrown by the Ming dynasty in the late 1300s. When that happens, chaos ensues and huge numbers of Yuan refugees — both Mongol and Chinese — flee to the Caucasus. There, they establish the Kingdom of Penglia as a bastion of Chinese culture in the West.

The Aldovian-Penglian War (we learn) ended in 1419, was fought over Silk Road trading routes, and included a land campaign in eastern Aldovia. The main Silk Road route passed through Anatolia and across the Bosporus into Aldovian territory, while a less popular alternative went north around the Caspian Sea, through Penglia, and across the Black Sea, which could allow traders to land in Belgravia and bypass Aldovia altogether. Aldovia’s war goal may have been to force Penglia to shut its borders to trade from China (which would have gone more smoothly without a language barrier).

In this scenario, Penglia is unable to cross through Belgravia to the north (its elected English king doesn’t want to anger the Aldovians while he’s fighting the Russians) or the Seljuk beyliks in Anatolia and is forced to invade Aldovia by sea. Aldovia’s navy continually disrupts Penglain naval supply lines, preventing Prince Jun from delivering a knockout blow. After years of inconclusive fighting, the two sides declare a truce.

The Status Quo

It also becomes obvious as you watch these movies that Aldovia’s monarchy still wields considerable power. We meet a prime minister, but we also see Richard personally managing his kingdom’s economic policy. Belgravia and Penglia seem to operate the same way. They aren’t absolute monarchies, but they aren’t the ceremonial figureheads either. Perhaps the best parallels in our timeline are Lichtenstein and Morocco.

That this form of government would survive into the present day on such a large scale suggests to me that, although America still won her independence, nothing like the French Revolution ever took place. Which means no Napoleon, no WWI, and no Hitler.

Perhaps the most striking detail we learn about the current state of geopolitics is that neither Aldovia nor Penglia has a standing army. This suggests a world far more peaceful than the one we live in.

A quick glimpse of a bank statement reveals that the euro (and therefore the European Union) exists in this timeline, but perhaps this EU formed much earlier than ours, and it’s clearly less heavy-handed in imposing neoliberalism. Is it too much to hope that the Netflix Christmas timeline has seen 500 years of European peace along with true national sovereignty?

Well, maybe. A Reddit user who goes by co209 took a good stab at mapping the rest of Europe and explaining how it got that way. In his telling, Aldovia, Belgravia, and Penglia fought alongside the U.K. against France, Germany, and Russia in two major 20th-century conflicts equivalent to our world wars. This would explain why Aldovia and Penglia don’t have standing armies — they were forcibly disarmed after losing the second one.

Ultimately, it’s a matter of interpretation whether Aldovia is a harmonious plurinational Catholic empire of farmers, shopkeepers, and dignified guild craftsmen or an unstable, repressive, impoverished aggressor state pouring money into public works to prevent the peasants storming the Christmas castle and stringing King Richard up like a sprig of mistletoe. You can make the case either way.

And that’s the real problem, isn’t it? Creating such a rich alternate universe while providing so little information about it is pure malpractice on Netflix’s part. Next time, they should throw the husbands a bone.

Grayson Quay is a Young Voices contributor based in Arlington, VA. His work has been published in The American Conservative, the Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, and The Spectator US.