Originally Authored at TheFederalist.com

In 2018, French President Emmanuel Macron made the dubious observation that educated women don’t choose to have many kids. “I always say: ‘Present me the woman who decided, being perfectly educated, to have seven, eight, or nine children,’” he said.

Catherine Pakaluk, a Harvard Ph.D. and Catholic University professor, immediately posted a picture of herself with her six children and started a viral hashtag #postcardsformacron, urging educated women with large families to send photos to Macron letting him know how wrong he was.

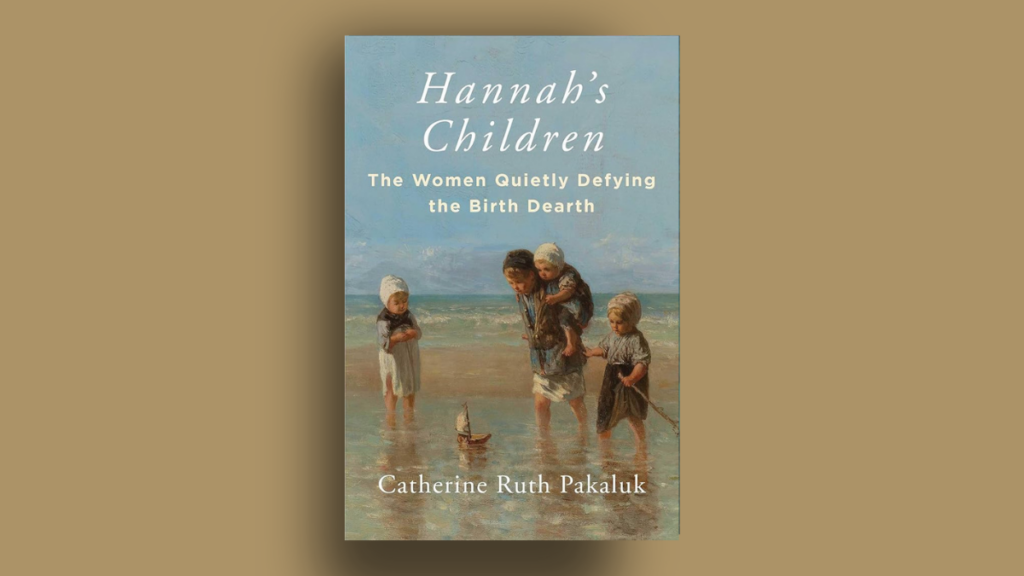

However, the subject of large families is a professional, as well as personal, concern for Pakaluk. Along with her colleague Emily Reynolds, Pakaluk has now conducted a uniquely experiential study over the course of several years and across ten American regions, dissecting the reason, meaning, and intentions behind large families through lengthy, relational interviews with 55 women who have five or more children. The results are chronicled in their new book, Hannah’s Children: The Women Quietly Defying the Birth Dearth.

While there is much to be said about the particular reasons people choose to have large families, Pakaluk writes that there is one beautiful commonality among these women:

I suppose it boils down to some sort of deeply held thing, possibly from childhood — a platinum conviction — that the capacity to conceive children, to receive them into my arms, to take them home, to dwell with them in love, to sacrifice for them as they grow, and to delight in them as the Lord delights in us, that that thing, call it motherhood, call it childbearing, that that thing is the most worthwhile thing in the world — the most perfect thing I am capable of doing.

Hannah

Pakaluk opens with the story of Hannah, a woman from a Reformed Jewish background whose search for meaning led her ultimately to procreation and the proliferation of family through child-bearing, what she called “this key to infinity.” At the time of her interview, Hannah had seven children, and described her choice to have a large family as a “deliberate rejection of an autonomous, customized, self-regarding lifestyle in favor of a way of life intentionally limited by the demands of motherhood.”

Throughout the book, Pakaluk refers back to this Hannah, tying her to the biblical Hannah of the Christian Old Testament, who suffered infertility until she offered her first child back to the Lord.

Like Pakaluk’s Hannah, the majority of the study’s subjects shared a similar expression of procreation as eternal and transformative – to the identity of the mother, the society of the family, and the potential extension of intrinsic values of faith and forbearance of individuals raised in large families impacting the greater world in the future.

Though some women in the study held doctorate degrees and worked in academia, their family habits often corresponded to those with less education and income. Pakaluk found that cross-sections of habits across socioeconomic divides grew alongside the size of the family. These families often grew around similar core values, hardships, and joys.

Expressive individualism

In Hannah’s Children, Pakaluk contextualizes the purpose and potential of the study through a lengthy discussion of the economics of family over time. She documents historically changing patterns of marriage in America, from the “rugged individualism” characterizing early American families to the twentieth century’s “expressive individualism … the self in contradistinction from the family.”

Despite diversity of backgrounds and means, the enablement of faith and a “dignified” life are common theme among the stories Pakaluk and her colleague share, as their study subjects “believe they have found,” rather than lost, themselves in having children.

“As it happens, in a two-child world trending to a one-child world, the desire for children and how it is charted in relation to competing human goods isn’t a small thing …” Pakaluk found. “There is no more economically significant question than where people come from, and nothing more deeply informs the way we order our lives together than the first society we experience: the family.”

The modern challenge to traditional and cohesive family roles has absolutely impacted family growth patterns, the book argues, and will likely continue to do so. And the declining population will impact future workforces, infrastructure, and entitlement programs far beyond basic demography.

“The political and economic consequences of these trends cannot be overstated,” Pakaluk writes. “Birth rates are falling because of tradeoffs women and households are making — tradeoffs between children and other things that they value.”

Of interest, Pakaluk notes, is the so-called “paradox of declining female happiness” evidently declining for the past five decades according to labor economists, as women continue to choose careers and limited children over large families.

Pakaluk reviews the institution of pro-natalist policies across the globe, finding that they unequivocally fail to produce long-term change.

“Cash incentives and tax relief won’t persuade people to give up their lives,” Pakaluk writes. “People will do that for God, for their families, and for their future children … Religion is the best family policy.”

Through her interviews, Pakaluk dispels the myth that women who have large families are unaware of and haven’t weighed the costs; that their choice to have many children is not reflective of personal desire or thought. The costs, both personal and literal, have absolutely been calculated by these women, Pakaluk found. Her subjects recognized the change in identity they would experience going against the birth dearth, the alternate lifestyle they would inhabit, the lack of “fitting in” in modern American culture.

But every woman interviewed conveyed that the greater good, the total benefit of having so many children, significantly outweighed any loss or missed opportunities. Some women believed they were receiving the greater gift, most believed they were pleasing God by accepting his blessings in children, and one mother specifically grew her family to please a beloved spouse.

Their Contribution

Pakaluk concludes that policymakers and economists would do well to recognize the sampling she surveyed, a “small but not insignificant demographic group,” she writes, “women … who see their children as their purpose, their contribution, and their greatest blessing. Women like them may never be a majority, but their stories have profound relevance for the domestic policy questions related to demographics, as well as for the deeper public dialogue about lifestyle patterns, individualism, rootedness and connectedness … and the future of the American experiment.”

Pakaluk’s deep personal interest in the large family and rigorous academic approach may shift minds and hearts to consider the cost benefit of the families with five or more children in America, leading to greater interest and societal support for what has come to be considered the outlier.

Ultimately, her “Hannahs” reiterate the ultimate and archetypal meaning of the family unit, reinventing cohesive community within the home against the tide of population depletion.

Ashley Bateman is a policy writer for The Heartland Institute and blogger for Ascension Press. Her work has been featured in The Washington Times, The Daily Caller, The New York Post, The American Thinker and numerous other publications. She previously worked as an adjunct scholar for The Lexington Institute and as editor, writer and photographer for The Warner Weekly, a publication for the American military community in Bamberg, Germany.

Ashley is a board member at a Catholic homeschool cooperative in Virginia. She homeschools her four incredible children along with her brilliant engineer/scientist husband.