Originally Authored at TheFederalist.com

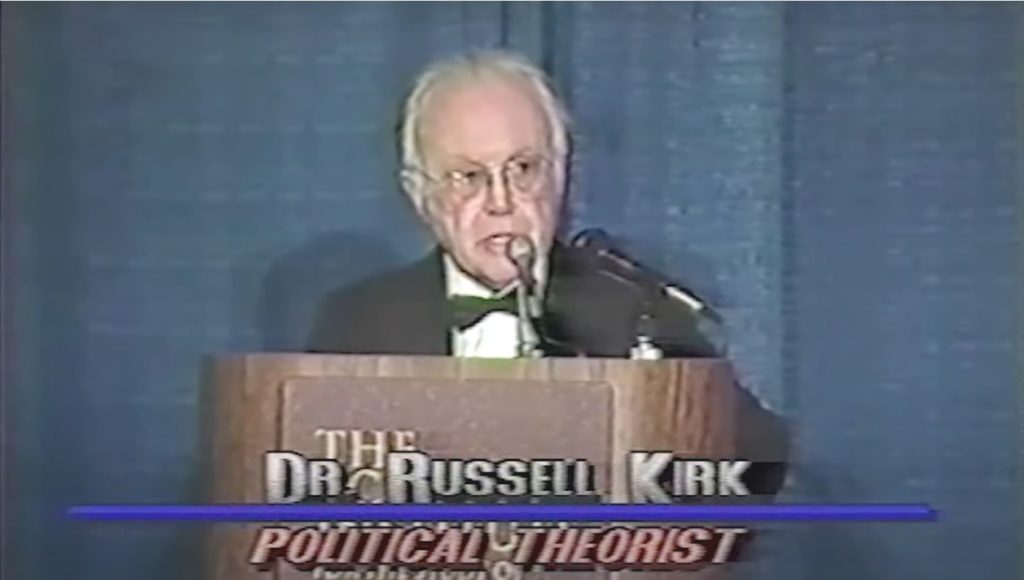

While a handful of writers and thinkers before him had adopted the term “conservative” and promoted it in their writings, like Peter Viereck in the 1940s, it was the publication of Russell Kirk’s The Conservative Mind in 1953 that brought the term into public parlance and prominence.

Michael Federici gives a brief but insightful introduction to the newly rereleased version of The Politics of Prudence, Kirk’s collection of essays first published in 1993 after the collapse of the Soviet Union and the end of the Cold War. The work attempted to present conservatism anew in an age now free from the ideological struggle of the Cold War.

Conservative Character

Federici notes that Kirk understood conservatism to be “a disposition of character rather than a collection of reified, abstract political doctrines. It is the rejection of ideology rather than the exercise of it.” This, too, is the understanding of conservatism laid out by the champion of conservatism in the 21st century, my former teacher Sir Roger Scruton.

This understanding may help one realize why conservatism fails as an ideology — because it is not an ideology. As Kirk humorously notes early on in one of the early chapters of this book, conservatives who attempt to ideologize conservatism make the first and most egregious error in understanding conservatism.

If, though, conservatives are united in “a disposition of character” and “rejection of ideology,” what is that “disposition” and what does the “rejection of ideology” entail?

Let us turn first to the character and disposition of the conservative as Kirk defines them. First and foremost, “the conservative finds himself in realm of mystery and wonder, where duty, discipline, and sacrifice are required.”

Second, the conservative accepts that the cosmos is governed by a transcendent moral order. This transcendent moral order serves as the basis of the mystery and wonder of existence, which makes possible the life of love. This disposition of love that guides conservatives is opposed to the modernist view of existence, “an arid and loveless realm” that “is a stage for the ego, with its appetites and self-assertive passions.”

Against Ideology and Centralized Power

Next, the rejection of ideology is principally opposed to the double threat of “an earthly paradise” and “centralized power,” which motivate totalitarian impulses.

Three of the chapters, originally lectures given by Kirk, illustrate these ideas. First, “The Errors of Ideology” explores the ideologue’s outlook and disastrous policies. The ideologue, Kirk explains, “thinks of politics as a revolutionary instrument for transforming society and even transforming human nature.” This outlook and ideological construction of politics is what the conservative rejects.

Second, Kirk’s brief but illuminating reflection on “The Politics of T.S. Eliot” helps the reader understand more fully the conservative disposition. The life and writings of Eliot reveal the conservative’s distrust of “centralized power” in any form, be it under “capitalism” or “socialism” or any other ism. The destruction of ethics and theology by practical utilitarianism has caused the despotism of merciless and heartless politics.

We are told, repeatedly, to keep God and morality out of politics. Yet, as Eliot insisted, society is bound together by common religion and a common ethical outlook. Without the recovery of the ethics of kindness and compassion, rooted in the Christian God, Western society runs to its own destruction under “the cult of the colossal.”

Neocons Now and Then

A final noteworthy chapter is Kirk’s assessment of the neoconservatives. This is a timely read today because the term neoconservative — often employed as a pejorative simply as “neocon” — has shifted wildly over the decades. But as Kirk shows, the original neoconservatives were, in fact, conservative during the Cold War.

The neoconservatives stood on the side of ordered liberty and civil society against encroaching bureaucratism in the 1960s, 1970s, and 1980s. Their founding and promotion of new journals, magazines, and eventual placement in serious newspapers of record showed the world, especially the scornful halls of academia, that conservatives could be quite intelligent, cultured, and mild-mannered — hardly the bores and vulgar imbeciles stereotyped by liberal academics and journalists. Lastly, the neoconservatives understood the grave danger of global communism at a time when many public intellectuals, writers, and even government officials in the United States wanted to back down from containment and sought rapprochement with the Soviets.

The neoconservatives were hardly the evil and sinister “neocons” of today’s polemical rhetoric. At the same time, Kirk also ended this chapter with the suspicion that they were changing into ideologues of imperialism, globalism, and “democratism.” Having written and lectured on this in the 1990s, Kirk was startlingly perceptive on where neoconservatives were going. If Kirk were alive today, he would agree with those who are now critical of the neocons for having abandoned their conservatism in favor of an imperialistic and globalist ideology.

Conservatism and Culture

In looking over the basic essence of Kirk’s writings, Federici states, “Culture, not politics or political power, is the first concern of the conservative.” This too is Scruton’s defense of conservatism and culture. But we must ask: What is culture?

Kirk defines culture as customs and traditions that operate in society. Culture is the emotional and ethical wisdom that customs and traditions within society communicate. They principally communicate through art, music, literature (especially poetry), and spiritual practices that teach us emotional and ethical wisdom.

The conservative, then, is concerned with preserving the wisdom of relational love that has been passed down generationally and developed by great thinkers, great artists, and great writers. This understanding of conservatism is broad in scope and invites those of us who may otherwise not share in conservative politics to be included in its ranks. And as Kirk implies throughout, there really isn’t an ideology of conservatism precisely because conservatism is not ideological in its political construction.

The latest edition of The Politics of Prudence is a worthwhile read, especially for a conservative movement adrift in the age of “democratism.” Kirk reminds readers who have not yet been indoctrinated into that ideology that democracy can be tyrannical too. There is nothing intrinsically noble about democracy — what makes a democracy noble is the virtuous citizens in a democracy.

Out of the ashes of democratic decline lay the possibility for democratic renewal with the recovery of that ethical, theological, and emotional wisdom to begin building again a humane society rooted in awe, wonder, and love. That is the struggle of the conservative in the 21st century.

Paul Krause is the editor-in-chief of VoegelinView. He is the author of “Finding Arcadia: Wisdom, Truth, and Love in the Classics” (Academica Press, 2023), “The Odyssey of Love: A Christian Guide to the Great Books” (Wipf and Stock, 2021), and contributed to “The College Lecture Today” (Lexington, 2019) and “Making Sense of Diseases and Disasters” (Routledge, 2022).