Originally Authored at TheFederalist.com

In an age filled with hostile propaganda against the nuclear family and devoted fathers in particular, it is worthwhile to ask why the celebration of Father’s Day persists.

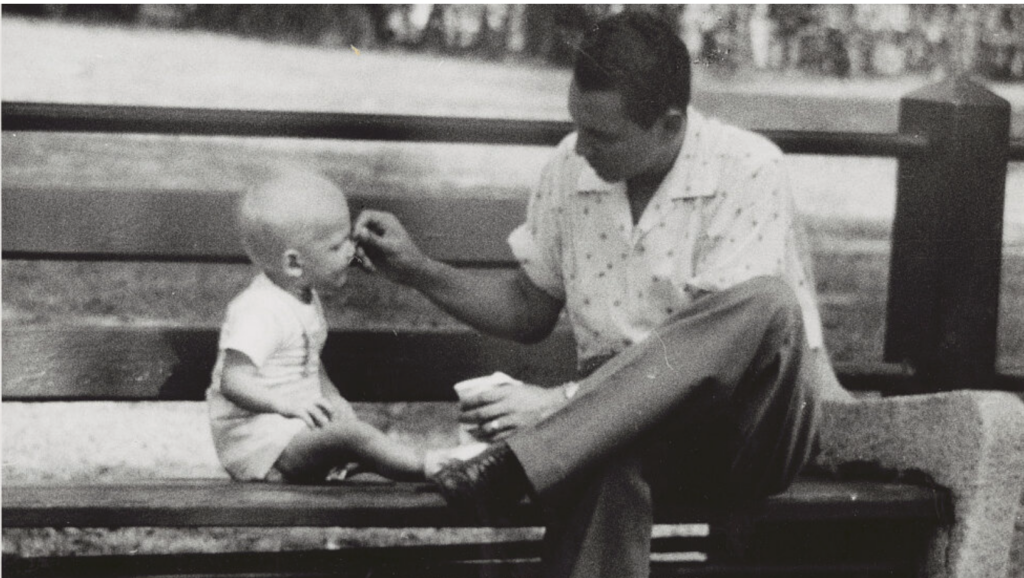

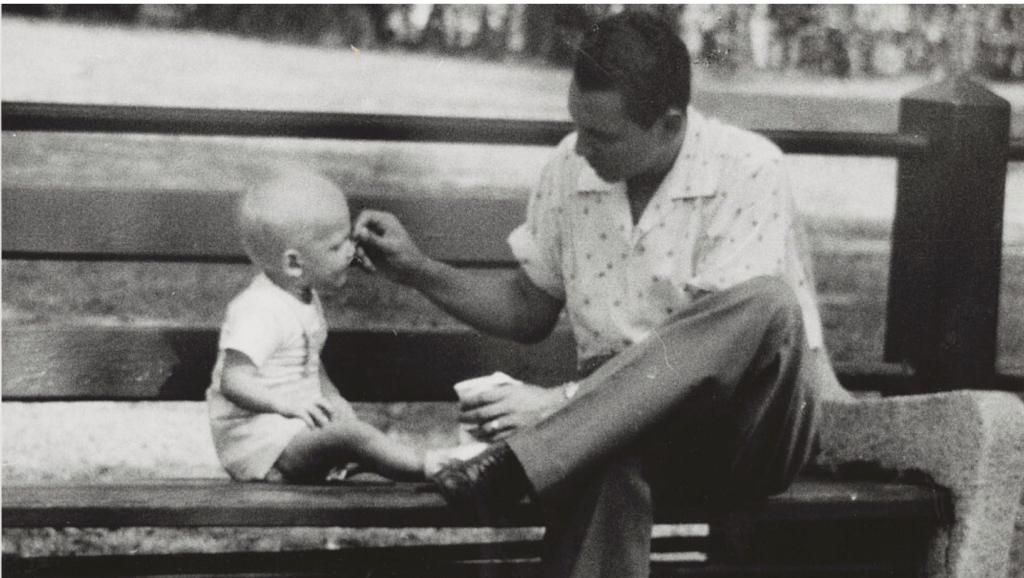

Most of us instinctively understand the connection between fatherlessness and social ills, such as crime, poverty, and mental illness. At the same time, we can see the calm and joy of children who are blessed with responsible and loving fathers.

Maybe those are reasons why the tradition of Father’s Day continues to hold sway in America, in spite of ideologues who hope to abolish responsible masculinity by labeling it as toxic, patriarchal, or a product of “white supremacy.”

Father’s Day also takes place at the height of June’s barrage of “Pride Month” agitation. Central to the “pride” agitprop is a massive campaign for the erasure of sex differences through gender ideology and the push for artificial reproductive technologies such as surrogacy that serve to remove fathers — as well as mothers — from the lives of children.

Still, the tradition of Father’s Day endures, despite the thanklessness of the work of good fathers by a culture that seems to reject the very notion of fatherhood. That’s because Americans actually love dads no matter how much the media instruct us to despise them.

Fictional Portrayals of Fatherhood Are Testaments to Father Hunger

Many stories in our popular culture are especially instructive on the importance of good fathers and a reminder of the father hunger children experience. In part, the term “father hunger” describes the emotional starvation, confusion, and frustration that comes with the loss of a father through death, absence, neglect, or abuse.

The Bible is filled with references that attest to the sorrows of the fatherless whom we are warned to treat well. Psalm 68:5 reads: “A father of the fatherless, and a judge of the widows, is God in his holy habitation.”

The father-child relationship is also central to countless works of great literature, including Ivan Turgenev’s novel Fathers and Sons, Harper Lee’s To Kill a Mockingbird, and Charles Dickens’ A Christmas Carol. There’s no shortage of movies that zero in on the critical role of fathers, including “The Lion King,” “Three Men and a Baby,” “Mrs. Doubtfire,” and “Field of Dreams.” However, you’ll notice that the production of such beloved stories seems to have faded in the 1990s. It’s no surprise that so few are produced these days.

Especially edifying about the yearning for good fatherhood is the role of the single father in so many old television shows in America. Beginning in the 1950s, there were numerous shows about the single dad — or dad surrogate — who responsibly raises bereaved children, offering them comfort and purpose in life.

The Mystique of the Widower Dad

Interestingly, the father who inspired the campaign for Father’s Day was himself a widower. At 16 years old, Sonora Louise Smart Dodd’s mother died, leaving Sonora’s devoted father to provide for her and her five younger brothers. The story goes that in 1909, when Sonora was listening to a Mother’s Day sermon in church, she felt that fathers should be honored as well. Her campaign for Father’s Day took six decades longer than Mother’s Day, which was officially recognized in 1914 by President Woodrow Wilson. It wasn’t until 1972 that President Richard Nixon signed the legislation recognizing Father’s Day — when Sonora Dodd was 90 years old.

The single father — particularly the widower father — seems to hold a special mystique in American stories. After recalling several TV shows that reflected that pattern, I did a little research. I discovered a wealth of information about them in Jim O’Kane’s website, TVDADS.com, where he traces the evolution of the single TV father decade by decade from the 1950s to the 2020s. I’ll focus here on a few popular single-dad shows I’m familiar with. They were produced during the 1950s and 1960s, which happens to be the same era that brought us shows about intact suburban families, such as “Ozzie and Harriet” and “Leave It to Beaver.”

The fathers in the single-dad shows were single mainly because the mother was dead. The widower mystique persisted even after divorce became more accepted in the 1970s and 1980s onward. For example, the father in the popular 1987-95 series “Full House” was a widower.

O’Kane points out that the household help often served the role of “stand-in mom,” such as the cook Hop Sing in the all-male Cartwright household of everyone’s favorite western, “Bonanza.” Ben Cartwright (Lorne Greene) was widowed three times, so each of his three adult sons — Adam, Hoss, and Little Joe — were literally brothers from another mother.

The same era brought us “The Andy Griffith Show” in which Mayberry’s Sheriff Andy Taylor is a widower who raises his young son Opie (Ron Howard) with the help of stand-in mom Aunt Bee. Another favorite was the widower Steven Douglas (Fred MacMurray) of “My Three Sons.” His father-in-law, the children’s grandfather, “Bub” (William Frawley,) also a widower, is the stand-in mom who wears an apron while running the household.

Another example is the “Courtship of Eddie’s Father” (Bill Bixby), which focuses on a widower whose son hopes to find a new wife for him. This theme recurs in other stories such as Patricia MacLachlan’s children’s book Sarah, Plain and Tall, and is a nod to the mother hunger a bereaved child will feel.

A few other shows with widower fathers in that early era were “Sky King,” “Flipper,” “The Rifleman,” “Gidget,” and even cartoons like “Dudley Do-Right.” Later series (in the 1970s) with different takes on the widower dad situation included “Sanford and Son” and “St. Elsewhere.”

Ever since, however, our culture has been trending toward a shallower portrayal of fathers who lack strong character or even a masculine identity. In recent decades, identity politics has inundated our culture with portrayals of fathers who identify as homosexual and/or transgender, such as in shows like “Modern Family” or “Transparent.” In large part, that’s because flooding popular culture with an LGBT focus — along with abolishing positive portrayals of traditional parenting — have been specific projects of the heavily funded GLAAD Media Awards since 1989.

But if we look back at the earlier portrayals of traditional fathers, we can sense the father hunger that’s at the root of Father’s Day as a beloved tradition. On the surface, those previous shows may have served as light entertainment. But they tell a deeper tale that reflects a persistent desire for good fathers as a source of healing and joy in the face of loss. When we celebrate Father’s Day, we acknowledge that undying reality.