The 30 Carbine and 223 Remington are two centerfire rifle rounds that both served the U.S. military in major overseas conflicts. Although the 30 Carbine and 223 Rem represent cartridges from two different eras, both have seen varying levels of success in the civilian market.

The 30 Carbine was introduced during WWII and served through the Korean War while the 223 Remington was introduced in Vietnam and remains the primary frontline cartridge for all branches of the American military to this day.

Although the 223 Remington fires a lighter bullet than the 30 Carbine, the 223 is superior to the 30 in all ballistic categories and is a perfect example of the advancements in rifle cartridge technology during the 20th Century.

In this article, we will evaluate the 30 Carbine vs.223 to help you understand the differences between the two and give you a clearer understanding of which cartridge is best for your shooting and big game hunting needs.

What is the difference between the 30 Carbine and the 223?

The difference between 30 Carbine vs 223 Remington is that the 30 Carbine round fires a heavier 30-caliber bullet while the 223 Rem fires a lighter 0.224” diameter bullet. Furthermore, the 223 is a more powerful modern bottle-necked cartridge while the 30 Carbine is less powerful and utilizes an older slightly tapered straight-wall cartridge design.

A Note on Nomenclature

Please note that within this article we will refer to the 223 Remington (223 Rem) and the 5.56x45mm NATO round interchangeably. There are differences between the two and you can read about them in this article: .223 vs 5.56

In short, a 223 Rem can safely be fired from a rifle or handgun chambered in 5.56, however the opposite is not true.

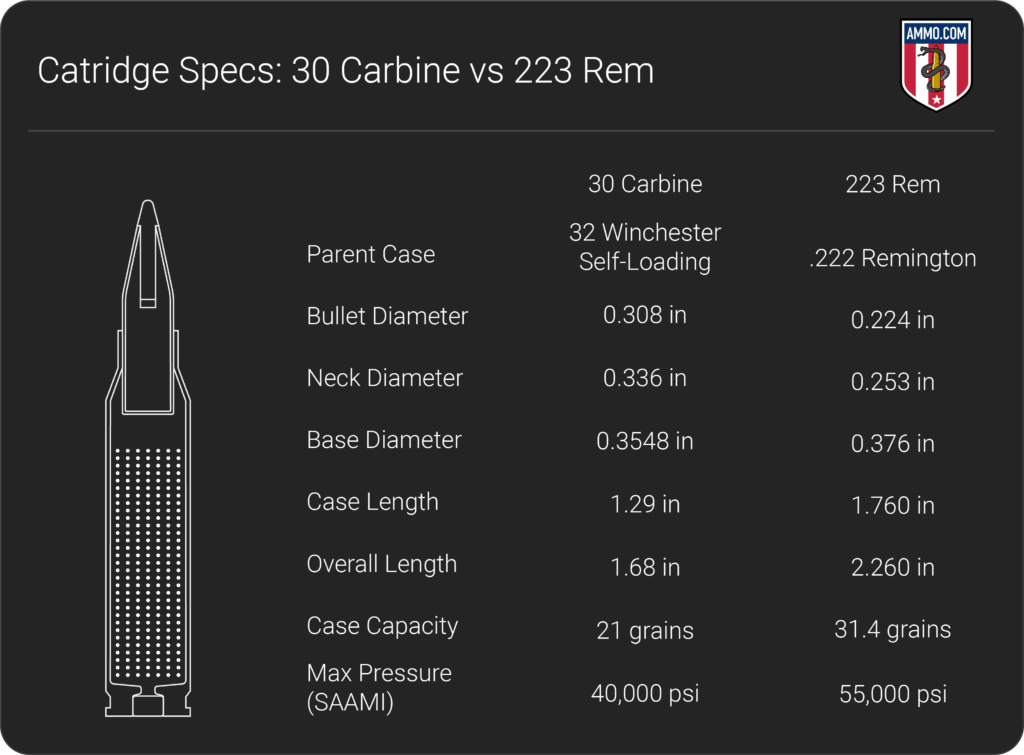

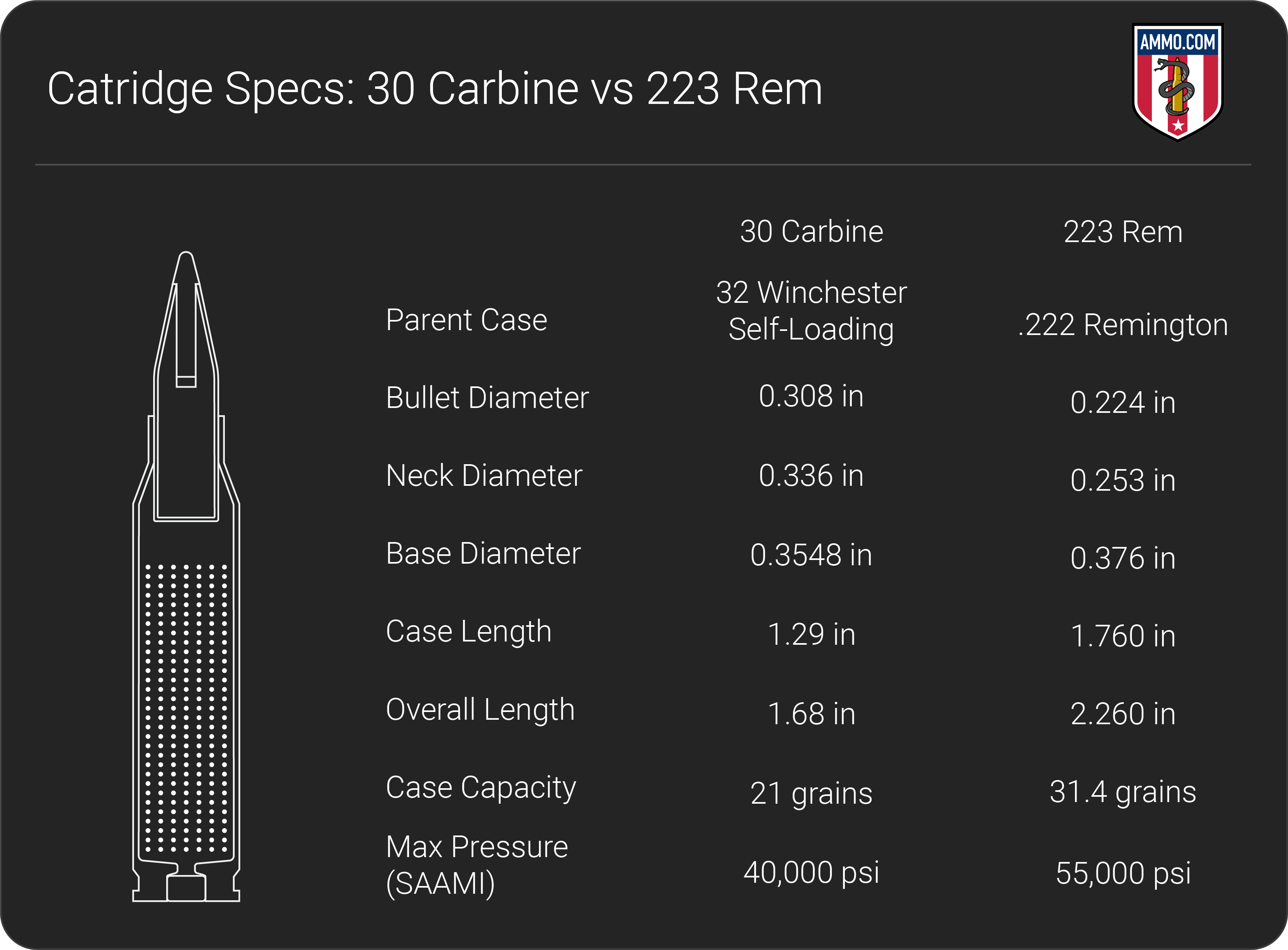

Cartridge Specs

When evaluating centerfire cartridges, it’s a good idea to analyze the cartridge specs to gain more knowledge of each.

Prior to America’s entrance into WWII, the U.S. Army wanted to provide support and mortar crews with a cartridge that was “more than a handgun but less than a rifle”. For these crews, carrying the heavier M1 Garand was inconvenient but they wanted more range and stopping power than the Thompson submachine gun or M1911 handgun chambered in 45 ACP could offer.

The resulting rifle was the M1 Carbine, which is essentially a scaled-down version of the M1 Garand and converted to use 15 or 30 round magazines. The 30 Carbine round was developed by necking down the 32 Winchester Self-Loading cartridge to fire a 0.308” diameter, 110 grain full metal jacket (FMJ) bullet.

The project was deemed a success and the M1 Carbine firing the 30 Carbine round was released in 1942 and served all branches of the U.S. military during WWII through the Korean War.

In contrast, development of the 223 Remington began in 1957 and the final design was submitted by Remington Arms to the Sporting Arms and Ammunition Manufacturers’ Institute (SAAMI) in 1962.

The development of the 223 Remington cartridge was a joint operation organized by the U.S. Continental Army Command between Fairchild Industries, Remington Arms, and Eugene Stoner of Armalite, using the 222 Remington as a parent cartridge.

The 223 Remington was chambered in the military’s new M16 assault rifle and later M4 Carbine and remains one of the most popular civilian cartridges chambered in the AR-15 semi-automatic sporting rifle.

Looking at these two rounds side-by-side, some of the differences are painfully obvious. The 223 Remington towers over the 30 Carbine by over a half an inch, as the 223 has a case length of 1.76” compared to 1.29” for the 30. In terms of overall length, the 223 Rem measures 2.26” long compared to 1.68” for the 30.

In terms of cartridge design, the 223 Remington utilizes a bottlenecked cartridge while the 30 Carbine was designed using a slightly tapered straight-walled cartridge.

Another major difference is the bullet diameter each cartridge fires. The 223 Rem fires 0.224” diameter bullets while the 30 Carbine fires a 0.308” diameter bullet.

The 223 Rem can fire a wide range of bullet weights, typically between 30 and 90 grains with the 50 gr, 55 gr and 62 gr factory loads being the most popular. In contrast, the 30 Carbine was designed to fire a 110 grain FMJ but can fire bullets as light as 85 grains and as heavy as 130 grains. Most factory ammo for 30 Carbine is loaded with 100 grain or 110 grain bullets.

One of the main reasons the 223 has a ballistic advantage over the 30 Carbine is that the 223 Rem has nearly 50% more case capacity than the 30. Capable of handling 31.4 gr of propellant, the 223’s case capacity dwarfs that of the 30 Carbine that can house 21 grains of powder.

With the added case capacity, the 223 Rem also is capable of handling significantly higher chamber pressures than that of the 30 Carbine. With a SAAMI spec 55,000 psi, the 223 has almost a 30% advantage over the 30 at 40,000 psi.

Recoil

Recoil is an important consideration when purchasing a new rifle as a round with heavy recoil will be more difficult to control and will slow your rate of follow up shots. The potential for flinching is also an issue for cartridges with heavy recoil.

Felt recoil will differ from shooter to shooter and is often dependent on firearm choice, stance, and your chosen factory ammo or handloads. However, free recoil is a more objective measure of how hard a cartridge hits based on firearm weight, muzzle velocity, powder charge, and bullet weight.

To compare the 30 Carbine vs 223 in terms of recoil we’ve selected the gold standard load for each cartridge. For the 30 Carbine we will consider the WWII M1 110 gr FMJ 1,990 fps military load and the M193 55 gr FMJ 3,200 fps military load for 223 Rem.

The firearms for this comparison will be a standard M1 Inland Carbine weighing 5.2 lbs and a standard AR-15 weighing 7 lbs for the 223.

Given these criteria, the 30 Carbine will have a free recoil energy of 5 ft-lbs compared to 4.25 ft-lbs for 223.

Although the 223 has a higher powder charge and muzzle velocity, its low bullet weight and heavier firearm help tame the already manageable recoil of the cartridge. On the other hand, the 30 has double the bullet weight and a lighter host firearm, which results is slightly higher recoil.

This is not to say that the 30 Carbine has oppressive recoil, quite the opposite actually, as most shooters would classify the 30 as having extremely low recoil. Both rifles are extremely easy to handle, a joy to shoot, and you can spend a whole afternoon plinking with either and not have a sore shoulder the next morning.

Although the 30 technically has higher recoil, both most shooters would describe both rounds as having low recoil and are excellent options for training new shooters on centerfire ammunition.

Muzzle Velocity, Kinetic Energy, and Trajectory

Previously I mentioned that the 223 Remington outperformed the 30 Carbine in terms of ballistics, but how big of a difference is it?

In this section, we will compare four popular factory loads for both cartridges.

For the 223 Remington, we will consider a Winchester 55 gr FMJ boat tail M193-clone as well as a Federal Fusion MSR 62 grain bonded Spitzer boat tail. For 30 Carbine, the M1 110 gr FMJ round nose military load will be compared with the Buffalo Bore 125 grain hard cast flat nose (FN) round.

When it comes to muzzle velocity there is simply no contest as the 223 Rem leaves the 30 Carbine eating its dust. At the muzzle, the M193 55 gr FMJ load for 223 held the highest velocity at 3,240 fps while the 62 gr Fusion came in second at 2,750 fps. The 30 Carbine rounds were the slowest at the muzzle, with the Buffalo Bore 125 gr lead FN clocking in at 2,100 fps while the M1 round was the slowest at 1,990 fps.

Not only is the 223 Rem faster at the muzzle, but it also conserves its velocity more effectively than the 30 Carbine. Both 223 factory loads were still supersonic at 500 yards, while the 30 carbine loads had gone subsonic between 200 and 250 yards.

Staying above the speed of sounds (1,125 fps) helps maintain a bullet’s trajectory, as it allows gravity less time to affect the flight path.

Speaking of trajectory, the 223 Rem simply slaughters the 30 when it comes to bullet drop. At all ranges 200 yards and above, the 223 Remington had less bullet drop than the 30. This is primarily due to the aforementioned supersonic limit of the 30 Carbine.

At 500 yards, the 30 Carbine loads had over three times the bullet drop of both 223 Remington rounds. This makes the 223 Rem a more accurate long range shooting cartridge with over double the effective range of the 30 Carbine.

One of the major critiques of the 30-caliber Carbine was its lack of stopping power. The 223 Remington/5.56 NATO has also had this critique leveled against it based on combat reports from Afghanistan and Iraq.

The 223 Rem has more foot pounds of kinetic energy at the muzzle and conserves its energy more efficiently downrange for both military loads. The M193 223 load has 1,282 ft-lbs of muzzle energy while the M1 110 gr FMJ 30 Carbine rounds has 967 ft-lbs.

The Buffalo Bore load for the 30 Carbine closes the gap in terms of kinetic energy, as it has 1,224 ft-lbs at the muzzle. This load was included in our comparison to showcase the highest levels of performance the 30 Carbine is capable of.

However, the 223 Rem’s efficient bullet design really shines at longer ranges, as it has nearly double the kinetic energy of the 30 rounds at 500 yards.

So, what conclusions can we draw from these results?

The 223 Remington is clearly the more effective long range cartridge. With higher muzzle velocity and a flatter trajectory, the 223 performs best for longer distance shots.

The bullet design of the 30 Carbine doesn’t do it any favors, as it hemorrhages velocity and kinetic energy at range. However, it has two times the bullet weight and leaves a considerably bigger hole than the diminutive 0.224” diameter 223 bullets.

This allows the 30 Carbine to be extremely effective in short-range engagements but is ill-suited for long range shots. The 30 has nearly double the kinetic energy of a mild 357 Magnum load or 45 ACP at the muzzle, so the military was successful at making a round that’s “more than a pistol but less than a rifle”.

Ballistic Coefficient and Sectional Density

Ballistic coefficient (BC) is a measure of how aerodynamic a bullet is and how well it will resist wind drift. Sectional density (SD) is a way to evaluate the penetration ability of a bullet based on its external dimensions, design, and weight.

The 223 Remington continues its dominance in ballistic coefficient thanks to its Spitzer boat tail bullet design.

The Winchester M193 223 factory ammo has a listed BC of 0.255 while the Federal Fusion load has an impressive 0.310 BC. In contrast, the 30 Carbine loads have considerably lower BC at 0.166 for the 110 gr FMJ and 0.126 for the 125 gr lead flat point from Buffalo Bore.

To put it simply, the 30 bullets are short, fat, not aerodynamic at all. On the other hand, the bullets fired by the 223 are considerably sleeker, resisting wind drift and air resistance more efficiently.

For sectional density, the 30 and 223 are relatively equivalent with the 30 having slightly higher SD for the 110 gr FMJ at 0.166 compared to 0.155 for the M193 load for 223. Sectional Density data was not immediately available for the Federal Fusion MSR or Buffalo Bore loads.

Although the 30 Carbine has a slight advantage in penetration over the 223, it is unlikely that most hunters or game animals will be able to tell the difference between them.

Hunting

The 223 Remington is one of the most popular varmint hunting cartridges in North America. A 223 long gun with a decent scope makes for a potent ground hog or coyote slaying machine, as it has incredibly low recoil and a flat trajectory.

The 30 Carbine also makes for a decent varmint cartridge for short-range shots. Although the trajectory of the 30 Carbine cartridge starts to resemble a rainbow at long range, there is something nostalgic about taking your Inland Carbine out into the woods for a little coyote hunting.

But what about whitetail?

The use of either cartridge for deer is a hotly debated issue at deer camps and hunting forums across the world.

The 30 Carbine has been used effectively for deer hunting since its introduction, however standard pressure ammo lacks the 1,000 ft-lbs of kinetic energy typically cited as required for whitetail. This goes to show that shot placement and selecting a quality hollow point or soft point bullet is more important than overall kinetic energy.

Furthermore, some hunters in states that allow the use of 223 Remington for deer hunting report good success with heavier 69+ grain bullets like the Hornady 73 gr FTX. However, many states prohibit the use of 0.224” diameter bullets for deer hunting.

Although both rounds can fell a whitetail with high-power loads and proper bullet selection, neither make for a good deer cartridge.

If we had to pick one, our choice would be the 223 Remington with a proper 69+ grain hunting bullet. However, 12 gauge shotgun slugs or a properly loaded 308 Winchester will make for better deer medicine than a 223 or 30 Caliber Carbine.

Ammo and Rifle Cost/Availability

The 223 Remington cannot be beat for ammo availability, price, and rifle options.

As one of the most popular centerfire cartridges in North America, the 223 Rem has numerous factory loads available for virtually any shooting application your heart desires.

Military surplus ammo is relatively easy to find and buying bulk 223 ammo can really help keep your overall cost per round to a minimum. The 223 has become so popular that ammo manufacturers have now started offering self-defense ammo such as Speer Gold Dots, Winchester PDX-1, and Hornady Critical Defense to cover all your home defense needs.

In contrast, 30 Carbine ammo is not nearly as popular as it was after WWII. Finding surplus 30 Carbine ammo is akin to finding a needle in a haystack and is considerably more expensive than it was after the war.

Modern ammo manufacturers like Remington, Hornady, Sellier & Bellot, and Winchester still make 30 Carbine ammo, but it much lower quantities than other ammo (like 223, for example). There are limited hunting ammo varieties available for 30 Carbine, traditional soft point and hollow point ammo can be had, but most 30 Carbine rounds will be loaded with FMJ’s.

In terms of cost, cheap plinking ammo can be had for around $0.60/round while premium hunting ammo ranges between $1.50-$3/round for 223. In contrast, 30 Carbine FMJ ammo will typically cost you about $1/round while self-defense or hunting ammo usually costs around $2 for each pull of the trigger.

Considering the 223 Remington can be fired from the most popular firearm in in United States, the semi-automatic AR-15, it cannot be beat in terms of rifle availability.

However, if you are not an AR-15 person there are still multiple options available to you. If you prefer a bolt-action rifle for some long range target shooting or varmint hunting, virtually every firearm manufacturer has at least one rifle chambered in 223.

For semi-auto options, the Ruger Mini-14 is perhaps the second most popular semi-automatic rifle for 223. The AK-platform has also been modified to fire 223/5.56 NATO and there are many other popular rifles chambered in the cartridge such as the Kel-Tec RDB, IWI Tavor, Steyr AUG, Galil, and many others.

In terms of AR-15’s, the sky is the limit as all the manufacturers from Anderson to Colt offer at least one rifle chambered in 223.

Pretty much the only type of rifle not chambered in 223 is a lever-action, as the rimless design and pointed bullets don’t play well with tubular magazines.

For the 30 Carbine, your rifle options are somewhat limited to the M1 Carbine.

However, these rifles vary in price considerably depending on their date and company of manufacture. Older WWII era rifles from Winchester, Rock-OLA, or IBM will fetch a premium, while newer production rifles from Auto Ordinance, Iver Johnson, Universal, or Inland can be had for a more reasonable price.

The 30 Carbine has also been adapted to several handguns, most notably the Ruger Blackhawk. The Taurus Raging Bull and AMT AutoMag III were also chambered in 30 Carbine, however these handguns have been discontinued and used models fetch a high price on the used market.

Reloading

Reloading is one method shooters use to reduce their overall cost per round and increase the consistency and accuracy of their ammo. Furthermore, handloads can be tailored to your rifle to meet your specific shooting needs.

Handloaders have been reloading 223 brass for decades at this point, meaning that there is load data available for virtually every bullet and powder combination that makes sense. In the same vein, 30 Carbine load data has been well flushed out and there are plenty of options available.

In terms of bullets, 0.224” diameter bullets are essentially a dime a dozen and extremely simple to find. Military surplus pulled bullets can be had for loading bulk 223 ammo at a low cost per round or you can load precision rounds for matches. Hunting bullets are also extremely inexpensive for 223 and made by reputable companies like Hornady, Berger, Barnes, Nosler, Sierra, and Federal.

If there’s one caliber that’s synonymous with “America” it must be the 0.308” diameter bullet. However, the bullets fired by the 30 Carbine are not as popular as those used by rounds like the 308 Winchester or 30-06 Springfield.

Due to its chamber design, the 30 Carbine cannot utilize Spitzer-style boat tail bullets like most 30-caliber cartridges. This means the 30 Carbine cartridge has to be loaded with round nose bullets that are more popular with lever-action rounds like the 30-30 Winchester.

Finding once-fired brass for 223 is an incredibly simple task as you can often find it lying on the ground at most ranges (just ask the shooter if you can have their brass before picking it up). For the 30, finding brass is a bit more difficult as it’s not as popular of a cartridge as it once was. Factory new brass can be had from companies like Winchester and Starline, while used brass is still available on the secondary market.

Final Shots: 223 vs 30 Carbine

The 223 Remington and 30 Carbine are two military cartridges that hail from two different eras of cartridge development.

The 30 Carbine is a product of the World War I and II era that brought us the 45 ACP, the 30-06 Springfield, and the 50 BMG. It is a round that filled a specific role for support soldiers who needed a lighter weapon for close-range combat.

By modern cartridge standards, the 30 is an anemic round that lacks the stopping power for whitetail deer and is best reserved for varmint hunting or plinking with an old M1 Carbine.

The 223 Remington is a modern cartridge that signaled a change in U.S. military combat policy. It’s an intermediate round that was built for low recoil, a flat trajectory, and be light enough so that soldiers could carry a lot of ammo into battle.

In the civilian sphere, the 223 is one of America’s beloved cartridges that is fired by the AR-15 carbine and is consistently in the top 3 cartridges sold in North America. It’s a versatile round that is the gold-standard for varmint hunting as well as target shooting and general plinking.

Although there is no denying the nostalgia factor of the 30 Carbine, our choice is the 223 Remington. It offers better ballistics with lower recoil and is less expensive to shoot.

No matter which cartridge you choose, make sure you stock up on ammunition here at Ammo.com and I’ll see you on the range!

30 Carbine vs 223: A Carbine Bullet Battle originally appeared in The Resistance Library at Ammo.com.

Source: The Daily Bell Rephrased By: InfoArmed