Originally Authored at TheFederalist.com

This month marks the 200th anniversary of the Monroe Doctrine. If celebration (or even acknowledgment) seems muted, that may be because policymakers and the public know little about the principles and grand strategy underlying the doctrine.

Few likely understand the doctrine because its meaning has been distorted throughout American history, especially in the Progressive Era by Theodore Roosevelt’s corollary. Some see it, for better or worse, as the beginning of America’s commitment to maintaining an international order by arms and diplomacy. But this is incorrect.

The Monroe Doctrine was not a blueprint for establishing an international order, or even for American involvement throughout the Western Hemisphere. It was an expression of the moral principles and strategic thinking that animated foreign affairs for the first century of our national existence. It is also the blueprint for returning to a realistic grand strategy that can preserve American liberty from threats foreign and domestic.

The Monroe Doctrine’s Origins

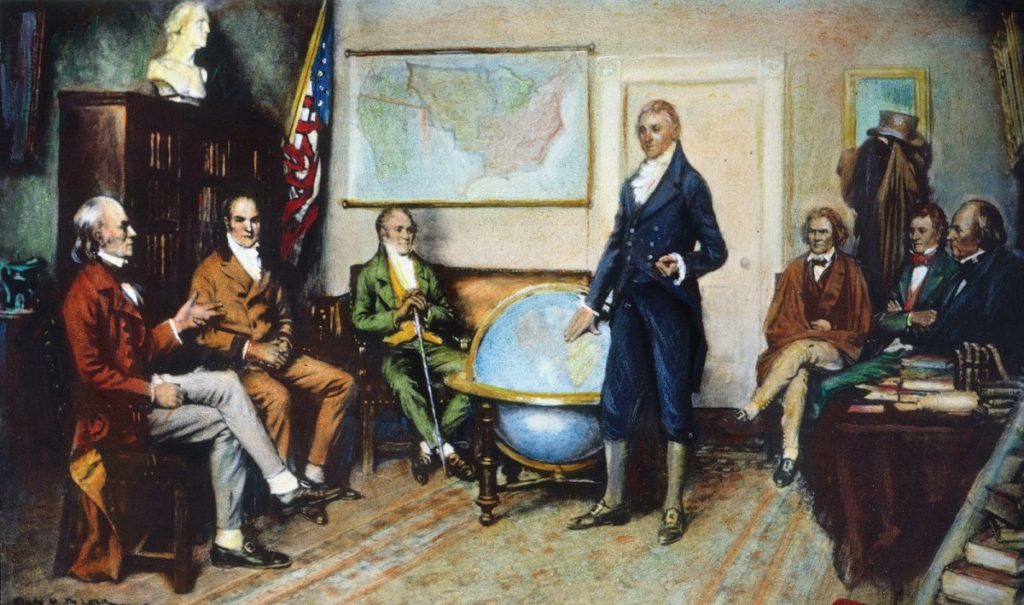

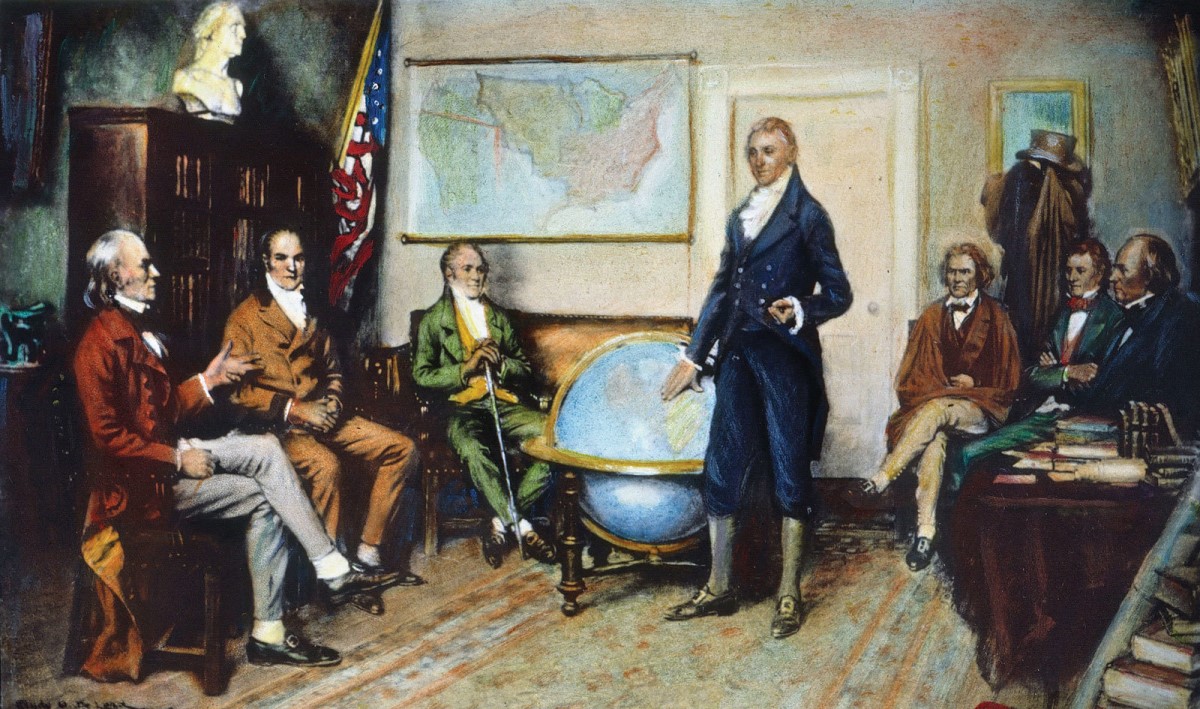

President James Monroe articulated what later became known as the Monroe Doctrine in his seventh annual message to Congress on Dec. 2, 1823. Its topic was the collapse of the Spanish Empire and the subsequent rise of independent nations in Latin America. Henry Clay and other leading statesmen saw this as an opportunity to push American-style republicanism abroad.

President Monroe and Secretary of State John Quincy Adams took a more cautious stance. Monroe declared a policy of neutrality in the wars between Spain and the newly independent republics of Latin America.

He also promised not to interfere with existing European colonies or the affairs of the Old World, warning that any European attempt to reassert control over those republics would be treated “as the manifestation of an unfriendly disposition toward the United States.” The Western Hemisphere would be off limits to any European nation that wished to maintain amicable relations with the United States.

Monroe was not promising to wage war on behalf of the new Latin American nations or republicanism. The Monroe Doctrine was rooted in two fundamental principles, one moral, the other strategic.

The Moral Principle of National Self-Rule

The first was the moral principle of national sovereignty. Monroe believed the right of a nation to govern itself was an axiom of the law of nations. He speaks of the “just principles” on which the United States recognized the independence of new Latin American republics, who elevated themselves to an equal status with the other powers of the Earth. By recognizing this equal status, nations can maintain peaceful relations with one another: “It is by rendering justice to other nations that we may expect it from them. It is by our ability to resent injuries and redress wrongs that we may avoid them.”

Nations can expect peace if they are willing to respect the citizens, territory, and commerce of other nations and are prepared to defend their own. Echoing the Declaration of Independence, Monroe wished that the Greeks, who were fighting a war of independence against the Ottomans, “would succeed in their contest and resume their equal station among the nations of the world.”

Yet kind words are all Monroe was willing to offer the Greek revolutionaries. It is up to each nation to secure sovereignty for itself. Monroe declares that “only when our rights are invaded or seriously menaced [do] we resent injuries or make preparation for our defense.”

America will not serve as the policeman of the world, nor as the guarantor of a community of nations. Monroe had no intention of imposing our form of government on any other part of the world, but only to protect Americans’ life, liberty, commerce, and sovereignty.

The strategic principle at the heart of the Monroe Doctrine is that a great power has an interest in keeping other great powers out of its immediate neighborhood. Different regions of the globe have unique strategic interests and concerns.

President Monroe warned the Europeans that “any attempt … to extend their system to any portion of this hemisphere” would be considered “dangerous to our peace and safety.” Monroe’s hemispheric thinking animated westward settlement: Americans were eager to reach the Pacific to close off the continent to future European colonies.

An American Principle Since the Founding

President Monroe was articulating a preexisting American grand strategy. As secretary of state, Quincy Adams had already expressed the administration’s commitment to restraint and neutrality in his famous address of July 4, 1821.

Adams praised the young American nation for having “abstained from interference in the concerns of others, even when the conflict has been for principles to which she clings… [America] goes not abroad in search of monsters to destroy. She is the well-wisher to the freedom and independence of all. She is the champion and vindicator only of her own.”

America cannot intervene on behalf of foreign causes, even just ones, because the “fundamental maxims of her policy would insensibly change from liberty to force.” Republican government requires restraint abroad. One that goes abroad in search of monsters to destroy would soon find a new monster at home: imperial government.

Adams’s exhortation for restraint and detachment from foreign wars followed President Washington’s advice in his Farewell Address. The first president similarly warned Americans to steer clear of permanent alliances and avoid permanent attachment or animosity toward any nation, which could obscure our true interests and make us unwitting servants of foreign governments.

“The great rule of conduct for us, in regard to foreign nations, is, in extending our commercial relations, to have with them as little political connection as possible,” Washington said.

A False Justification for Nation-Building

The strategic principle embedded in the Monroe Doctrine can be traced back to the beginning of the nation. Arguing in favor of a firm constitutional union backed by a powerful navy in Federalist No. 11, Alexander Hamilton outlined what could be called a proto-Monroe Doctrine. He writes: “The world may politically, as well as geographically, be divided into four parts each having a distinct set of interests.”

Europe, he goes on to say, has successfully extended its power over the other three parts — Asia, Africa, and the Americas — and could continue to do so if left unchecked. Hamilton’s solution was not to wage preemptive war or impose sanctions against Europe, but to create “one great American system” — a union of states powerful enough to control the Atlantic seaboard and counter European economic and political influence in the hemisphere.

How, then, did the Monroe Doctrine come to be interpreted as a justification for nation-building and intervention abroad? As Walter McDougall argued, 1898 marked the decisive turning point with the Spanish-American War. The United States embarked on a moral crusade to end the Spanish colonial government in Cuba and assumed imperial ambitions by the end of the war.

With the acquisition of the Philippines and other Spanish colonies, America for the first time governed territory that was never intended to gain statehood. Progressive imperialists like Sen. Albert Beveridge claimed the principles of consent and national sovereignty in the Declaration of Independence applied only to civilized nations, and that we have a moral duty to “administer government among savage and senile peoples” for their own good.

Today’s interventionists may not speak of savage peoples, but modern nation-building follows the spirit of early Progressive imperialism in assuming that the founding principle of national sovereignty is outdated.

The Roosevelt Corollary

Amid the Progressive transformation of foreign and domestic policy, President Theodore Roosevelt issued his 1904 corollary to the Monroe Doctrine in his fourth annual message to Congress. Roosevelt claimed the right “to the exercise of an international police power” over Latin American nations that failed to uphold the standards of civilization. Although the president claimed we can better promote “the general uplifting of mankind” by tending to our own affairs, he also spoke of rare, extreme cases “in which we could interfere by force of arms as we interfered to put a stop to intolerable conditions in Cuba.”

While Roosevelt’s message contains some elements of moderation and restraint, it is wrong to call it a corollary to the Monroe Doctrine. “Transformation” would be a more accurate term. Roosevelt stripped the doctrine of its moral core — the right of national sovereignty — and created a new right for the United States to interfere in the domestic politics of other nations. Once a republic assumes the right to impose upon other nations its own standard of civilization, it no longer has a moral safeguard to prevent its slide into empire.

The Roosevelt Corollary cemented the interventionist turn in American foreign policy. It is a short walk from Roosevelt’s assertion to Woodrow Wilson’s quixotic call to make the world “safe for democracy” through armed intervention in the First World War. From there, it is another short walk to George H.W. Bush’s commitment to use American firepower “to forge for ourselves and for future generations a new world order” and to his son’s promise “to seek and support the growth of democratic movements and institutions in every nation and culture, with the ultimate goal of ending tyranny in our world.”

Lessons From the Monroe Doctrine

What lessons can we learn from the Monroe Doctrine today? Some have called for invoking the doctrine to counter the threat of Chinese influence in the Western Hemisphere. No doubt, there are good reasons to keep powerful rivals out of our backyard, and the Monroe Doctrine does speak to the strategic need to maintain our sphere of influence.

However, the more relevant lesson from the Monroe Doctrine is the need to return to the moral principle of national sovereignty. Once American policymakers lost sight of this principle, they lost sight of the limits of intervention.

Wilson’s war to make the world safe for democracy paved the way for an even bloodier world war. The invasions of Iraq and Afghanistan cost trillions of dollars and thousands of American lives and failed to build liberal democracies in the Middle East. Interventions in the Libyan and Syrian civil wars created a protracted migrant crisis and, once again, failed to deliver on their humanitarian promises. The billions of dollars of American armaments sent to Ukraine have only prolonged a brutal war between two Eastern European oligarchies and driven Russia further into China’s arms.

The moralistic internationalism that has animated much of the last 125 years of American foreign policy has also opened the door to foreign influence. From the British government’s Bryce Report in 1915 to Nayirah Al-Sabah’s phony testimony of Kuwaiti babies being ripped from incubators in the lead-up to the Gulf War, foreign governments have fabricated atrocities to drag America by its heartstrings into costly wars. Reasserting national sovereignty as a moral principle and detachment from foreign conflicts as a strategic imperative are the necessary preconditions to a sensible foreign policy.

America First Foreign Policy

The ultimate aim of the Monroe Doctrine was to secure the conditions for liberty in our own nation. Intervention abroad sets the stage for imperial politics at home.

As Angelo Codevilla noted, the national security state acts as a praetorian guard, subverting the will of elected officials (and, by extension, the people), whenever it believes its preferences are threatened. Protracted engagement overseas feeds the budgets and political capital of unaccountable agencies and bureaucrats.

The CIA has spied on the Senate Intelligence Committee out of fear of civilian oversight. Unelected officials such as Miles Taylor in the Department of Homeland Security and Jim Jeffrey in the State Department have covertly disrupted presidential policies that conflicted with their policy preferences. Quincy Adams warned our governing principles could change from liberty to force, and the escalating use of surveillance, infiltration, and repression against opponents of the Biden administration prove him right.

Some will undoubtedly argue the Monroe Doctrine is outdated in a globalized age. Yet the oceans that insulated America from her great power rivals in the 19th century continue to do so today. Our fleets and nuclear umbrella deter peer competitors from threatening our soil. Whatever risks may come with returning to the restrained geopolitics of the Monroe Doctrine are outweighed by the proven consequences of going abroad in search of monsters to destroy.

Casey J. Wheatland is a senior lecturer of political science at Texas State University. He holds a Ph.D. from Hillsdale College and is a former Publius Fellow at the Claremont Institute.